Black Swans: Burke, Keynes, Taleb

Branco Milanovic has a very interesting post on why Nassim Nicholas Taleb is “one of the most important thinkers today.”

Milanovic is a professor of economics at CUNY, a leading student of income inequality,  and not one, I suppose, to lightly hand out such praise. Taleb, you recall, is a former derivatives trader, statistician, scholar, and author of such popular works on risk and uncertainty as ‘The Black Swan’ and ‘Antifragile.’

and not one, I suppose, to lightly hand out such praise. Taleb, you recall, is a former derivatives trader, statistician, scholar, and author of such popular works on risk and uncertainty as ‘The Black Swan’ and ‘Antifragile.’

Milanovic explains how “Taleb has succeeded… in creating a full system that goes from empirics to ethics, a thing which is exceedingly rare in the modern world.”

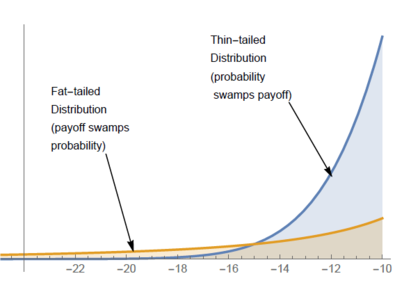

First, Taleb has done probably as much as anyone to show how extreme outcomes – ‘Black Swans’ – are much more likely and important than we commonly assume, especially for social processes. Technically speaking, we underestimate the size and likelihood of extreme events because we commonly misapply the ‘thin-tailed,’ normal or Gaussian (“bell curve”) probability distribution in many contexts that are really governed by highly skewed and ‘fat-tailed’ distributions.

In ‘Black Swan’ Taleb provides many entertaining examples of the difference between processes governed by thin-tailed distributions (‘Mediocristan’) and fat-tailed distributions (‘Extremistan’).

“Assume that you round up a thousand people randomly selected from the general population and have them stand next to one another in a stadium… Imagine the heaviest person you can think of and add him to that sample. Assuming he weighs three times the average, between four hundred and five hundred pounds, he will rarely represent more than a very small fraction of the weight of the entire population (in this case, about a half of a percent)… I can state the supreme law of Mediocristan as follows: When your sample is large, no single instance will significantly change the aggregate or the total...

“Consider by comparison the net worth of the thousand people you lined up in the stadium. Add to them the wealthiest person to be found on the planet—say, Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft. Assume his net worth to be close to $80 billion—with the total capital of the others around a few million. How much of the total wealth would he represent? 99.9 percent?... In Extremistan, inequalities are such that one single observation can disproportionately impact the aggregate, or the total.”

Here is another example from Taleb’s technical work-in-progress ‘Silent Risk’:

“One often reads in the press that ‘more Americans slept with Kim Kardashian than died of Ebola’ or… ‘Terrorism kills far fewer people than falls from ladders - the real threat is our overreaction’. Aside from ignoring the fact that it is vigilance and overreaction that lower such casualties, there is a method to compare risks without falling for naïve empiricism… Take a number K, say 100, 000. Which has a higher probability of exceeding K, Ebola victims or #x : the number of people who spent significant time between bedsheets with Kim Kardashian? Likewise the probability of the number of people falling from ladders tripling next year is of the order of 10-14 … so its probability of exceeding K is astronomically lower, while the number of American killed by terrorists is not subjected to such bounds.”

Second, Taleb explains how the prevalence of fat-tailed phenomena restricts or qualifies our ability to know the world, an epistemological concern. As Milanovic notes, “These are the phenomena where the averages carry very little informational content, and even variances do not necessarily mean much … We are dealing here with what Taleb calls the ‘fourth quadrant’, the unknown unknowns.”

Third, because of these limitations, Taleb concludes that, as a means of learning about the world, we should prefer an observational, inductive, ‘tinkering’ approach to a top-down, theory-heavy, deductive approach. Taleb extends this insight to desirable properties for institutions. Those that are the result of a long process of evolutionary trial and error and gradual tinkering will be not only more robust to shocks, but also ‘antifragile,’ or able to prosper under extreme volatility, compared to institutions built on theoretical systems and logical deductions. The British 'mother of parliaments' still putters on, but the Supreme Soviet is long gone.

This is a conservative insight. Milanovic comments that Taleb has arrived at a “conservative political philosophy, similar to Edmund Burke’s (whom he does not mention): institutions should not be changed based on deductive reasoning; they should be left as they are not because they are rational and efficient in an ideal sense but because the very fact that they have survived a long time shows that they are resilient. Taleb’s approach there has a lot in common not only with Burke but also with Tocqueville, Chateaubriand and Popper (whom he quotes quite a lot).”

This is a conservative insight. Milanovic comments that Taleb has arrived at a “conservative political philosophy, similar to Edmund Burke’s (whom he does not mention): institutions should not be changed based on deductive reasoning; they should be left as they are not because they are rational and efficient in an ideal sense but because the very fact that they have survived a long time shows that they are resilient. Taleb’s approach there has a lot in common not only with Burke but also with Tocqueville, Chateaubriand and Popper (whom he quotes quite a lot).”

John Maynard Keynes is not usually considered a conservative thinker. But, like Taleb, he was deeply interested in probability, which may have contributed to his appreciation for Burke’s conservative ideas. In 1904 Keynes wrote a prize essay on “The Political Doctrines of Edmund Burke”, which is unpublished, apparently, but which Keynes’ biographer Robert Skidelsky quotes from in the Penguin “Essential Keynes”:

“Our power of prediction is so slight, our knowledge of remote consequences so uncertain, that it is seldom wise to sacrifice a present benefit for a doubtful advantage in the future. Burke ever held, and held rightly, that it can seldom be right to sacrifice the well-being of a nation for a generation, to plunge whole communities in distress, or to destroy a beneficent institution for the sake of a supposed millennium in the comparatively remote future. We can never know enough to make the chance worth taking, and the fact that cataclysms in the past have sometimes inaugurated lasting benefits is no argument for cataclysms in general. These fellows, says Burke, have ‘glorified in making a Revolution, as if revolutions were good things in themselves.’”

“Our power of prediction is so slight … We can never know enough …”. Yes, this sounds about right.

[First exhibit: from Figure 1.6 in Nassim Nicholas Taleb's technical work-in-progress Silent Risk.

Second exhibit: Portrait of Edmund Burke by James Barry, Provost’s House, Trinity College, Dublin.]